“The common end of all narrative, nay of all, Poems is to convert a series into a Whole… to make… a circular motion — the snake with its Tail in its Mouth.” — Samuel Coleridge, Collected Letters IV (1815)

Accomplicing that plot device, surprise,

the day shone royal blue. Our Sunday walk

assumed pedestrian guise until her lies

constricted near Unending Books. In mock-

submissive tone, she sighed: “Please let me be

right here, outside our favorite used-book store.

It’s where we met. All circles close a door.

That’s symmetry — the poetess in me.”

I pondered the reflection of my self

on Austen, half-price-off; then for a song,

the poets, ancient children, on a shelf

set up on crumpled velvet. All along,

this princess had availed a serpent-guide.

I was the frog to her formaldehyde.

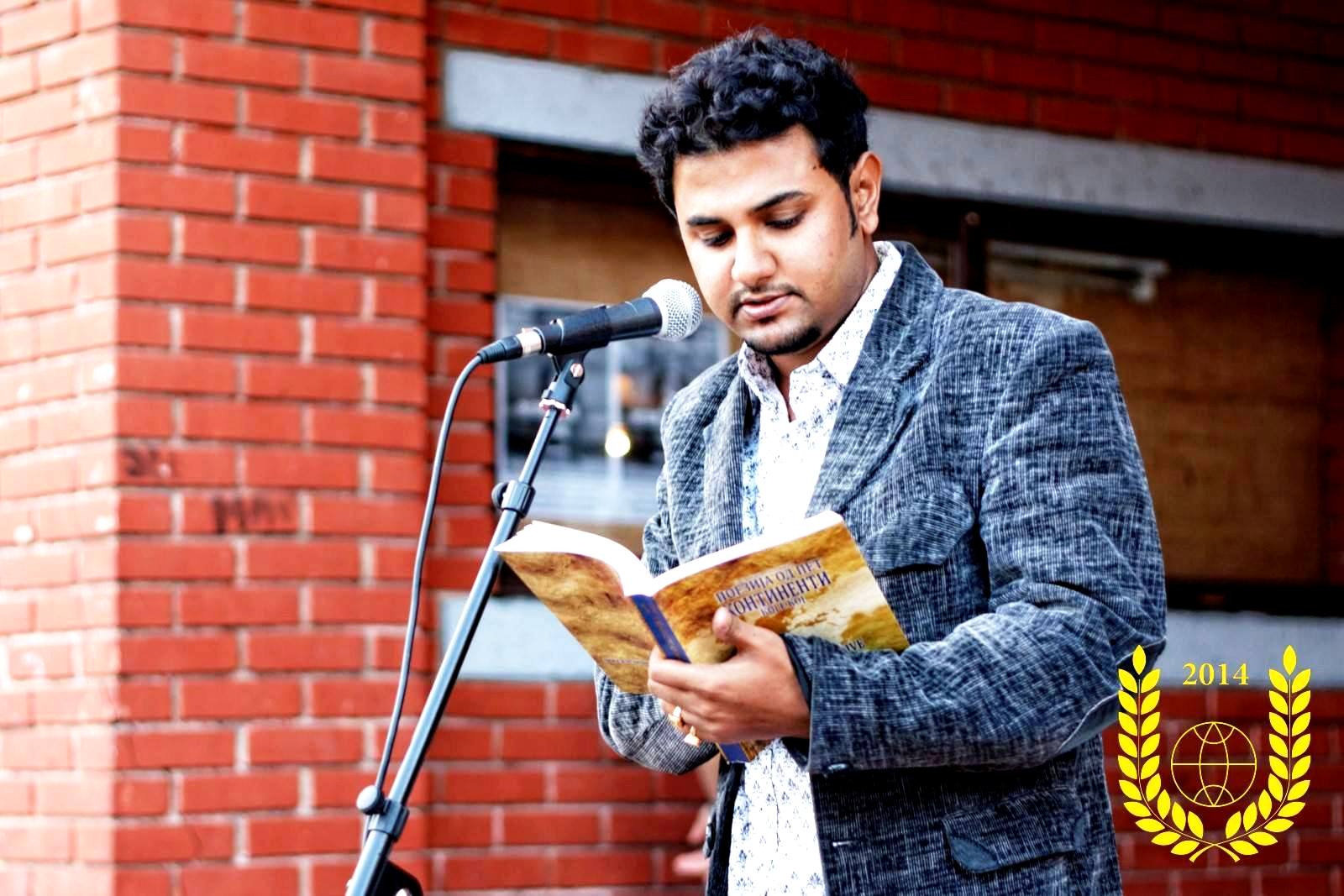

NORMAN BALL (BA Political Science/Econ, Washington & Lee University; MBA, George Washington University) is a well-travelled Scots-American businessman, author and poet whose essays have appeared in Counterpunch, The Western Muslim and elsewhere. His new book “Between River and Rock: How I Resolved Television in Six Easy Payments” is available here. Two essay collections, “How Can We Make Your Power More Comfortable?” and “The Frantic Force” are spoken of here and here. His recent collection of poetry “Serpentrope” is published from White Violet Press. He can be reached at returntoone@hotmail.com.

(first appeared in Angle, Volume 3, Issue 2, Autumn/Winter 2014)

Norman Ball ‘Serpentrope’

White Violet Press, 2013

If I told you that most of the poems in Norman Ball’s Serpentrope are metered and rhymed, with four-fifths of them sonnets, you’d probably get the wrong idea. So we’ll consider that a bit later. Instead, let’s begin with the eclectic nature of the book.

I believe Serpentrope is the only poetry book published to date that contains poems on the topics of: Civil War battle fatigue; formal poetry in its relation to a famous wardrobe malfunction; and Aleister Crowley’s Cult Of Lam. The poems often display a love of detail—historic and current—as in this excerpt from ‘Observations of a Civil War Surgeon As Night Falls’:

Cattail and catgut duel within the marsh that dads

the Susquehanna east of York. Two minstrels,

facing off, interpret harsh conditions with guitars.

The river’s fork

accompanies with stiff, percussive reeds.

Ball’s poems stem from an obvious intelligence, and that seems appropriate. Often they mimic the way that neurophysiologists characterize our thinking process: as the firing up of nodes of meaning that excite other nodes in a sort of spreading activation, until a whole pattern of nodes—perhaps previously unconnected—fires together, leading to new connections and novel insights. None of this, according to the theory, is sentential. Sentences come later. This mental commotion underlying conscious thought is echoed in Ball’s poetry in passages such as this from the poem ‘Formal Spat ‘:

… One dares

not ride a colleague’s time-worn rhyme. Left-hand feet

may dangle. Diction may rankle, stubborn

with vague intent. Relax. Sonnets can’t meet

the rent with a metered stick…

Or this, from ‘It Was A Totter From The Start’:

The duty steeped itself in stand-up time, a

rope to drag the day upon itself

with busying to coax the febrile mind

from thought, to book, to browse, to empty shelf.

Many of Ball’s poems employ puns, allusions, and apparently unrelated content. The result is that they often excite neurons in our minds that, at least for me, are firing together for the first time. This type of mental fireworks can be fatiguing, and it may be that the best way to read Serpentrope is to limit oneself to two or three poems a day.

I may have mentioned that Ball’s poems take on a wide variety of subjects. Serpentrope includes poems centered on: the cartoon character Dilbert rendered in a Hilbertian sonnet; dropping poems by airplane on Afghan villagers in wartime; and ballerinas with bulimia. And often the poems render their subjects in witty, punning, allusive lines. Like these in an excerpt from the poem about Dilbert, the cartoon engineer working in a cubicle in a large corporation:

… Dilbert stirs this pot with lead

balloons. His poker-face is barely drawn

by nine. Outside the box, Big Bosses rake

trapped miners over coals while overhead

a phosphor-fingered entity has sawn

animal spirits squarely down to size —

three taut frames. Dilbert’s zeppelin subsides.

Of course, like real-world explosions, explosions of meaning can do damage if not controlled, and Ball is an explosives expert. These poems are nearly all contained in meter and rhyme, and now that you have a feel for the content, it can more fully be revealed that most of them are in sonnet form. The interplay between the subject matter, the allusions, and the forms adds another dimension to the experience of reading Ball’s work — a dimension that I believe elevates the wild content by the mere fact of being under such control.

Given the eclectic nature of Serpentrope (I should mention that it contains poems on the subjects of: belly fat; the fate of a member of the band REO Speedwagon; and the turbulent life of the prophet Isaiah), it should be noted that the book also contains some recurring themes.

The most explicit is that of the snake Ouroboros, a topic treated in several of the poems and the subject of an essay included as an appendix to the book. The image of the snake with its tail in its mouth, sometimes curled protectively around the earth and sometimes a part of it, has, according to Ball’s essay, fascinated him for years. In the poem ‘Ouroboros,’ Ball portrays the snake in a menacing way:

…The proper name’s Hell-

that cool, wrapped bitch— trite circle. Let her clasp

sweet tail in teeth. All gray divides sell

foot-in-mouth diversions. I will have my foe just-so.

Discrete obsession. Damn

all demons who arrive. The golden calf,

zirconia stalking horse, is lamb

I dressed for slaughter…

But it is not always so. Sometimes the snake is a hoop snake rolling along, and sometimes it is a snake completing a cosmic circle.

Another theme in the book is that of human relations. Serpentrope does not contain a love poem as I understand them, but there are multiple renderings of soured or difficult relations between couples. The concluding lines from the poem ‘Endure’ are one example:

… We gratify

what synapses are lit. Hullabaloo

is all that floats above—mere atmosphere.

What anchors? That’s a fixity less clear.

The reader of Serpentrope will soon see that Ball is no sentimentalist. Poetry itself forms another theme in the book. There are multiple poems on the topic of poetry, a theme that first appears in the inscription that begins the book:

Teach a man to write poetry

and he will starve forever.

Ball begins the poem ‘Twickenham Stadium’ by stating ‘I’m not so much a poet as a wit,’ and then proceeds to compare himself and his work to the career of the American baseball player Harmon Killebrew, a Hall of Famer who, nonetheless, had some years with low numbers of runs batted in. Poets writing poems about poetry can be trying, but Ball pulls it off—in this case, with extended comparisons between his work and baseball. Let’s consider two techniques that I particularly admire in Ball’s work. The first is the clever enjambment, and the second is the killer concluding couplet. One of my favorite poems in the book is the sonnet ‘At the Funeral of a Former High School Crush,’ which begins with the wonderful enjambment

I memorized her purple halter top to bottom…

The poem then describes time shared together in physics class, and concludes with this couplet that brings us back to the funeral of the title:

They found her with her head arrayed in glass

flung forward like a weightless, prescient gas.

I love that couplet. And many others in Ball’s book. One more example. In the poem ‘Slither,’ that begins with a quote from Coleridge referencing Ouroboros, the narrator learns that a walk with his lover is actually her way of finding a suitable place to terminate their relationship. She has chosen the bookstore where they met to end things in Ouroboran fashion, and the poem itself concludes:

… All along,

this princess had availed a serpent-guide.

I was the frog to her formaldehyde.

Serpentrope is a book of formal poems that really doesn’t feel like one. It treats a wide variety of topics (I should mention that Serpentrope contains poems on: the antediluvian apostasies of G. H. Pember; the difficulties in Ireland; and the nature of testimony in the aftermath of the mortgage meltdowns). There are wonderful gems, couplets, and full poems that sparkle and explode. Serpentrope is a virtuoso performance by a poet of wide-ranging intelligence whose careful use of form adds considerable impact to his work.

–David Davis

editor@artvilla.com

robin@artvilla.com

www.facebook.com/PoetryLifeTimes

www.facebook.com/Artvilla.com